Archaeologists and historians have launched an investigation into a deadly naval drama which unfolded more than a century ago off the coast of Yorkshire.

For the past 103 years, a German submarine (UC47) from the First World War has lain largely forgotten at the bottom of the North Sea 22 miles off Flamborough Head.

Sunk by the royal navy in November 1917, she symbolises a crucial turning point in that epic conflict’s war at sea.

But now, archaeologists have, for the first time, started surveying the vessel – in an attempt to unravel the full story of her sinking.

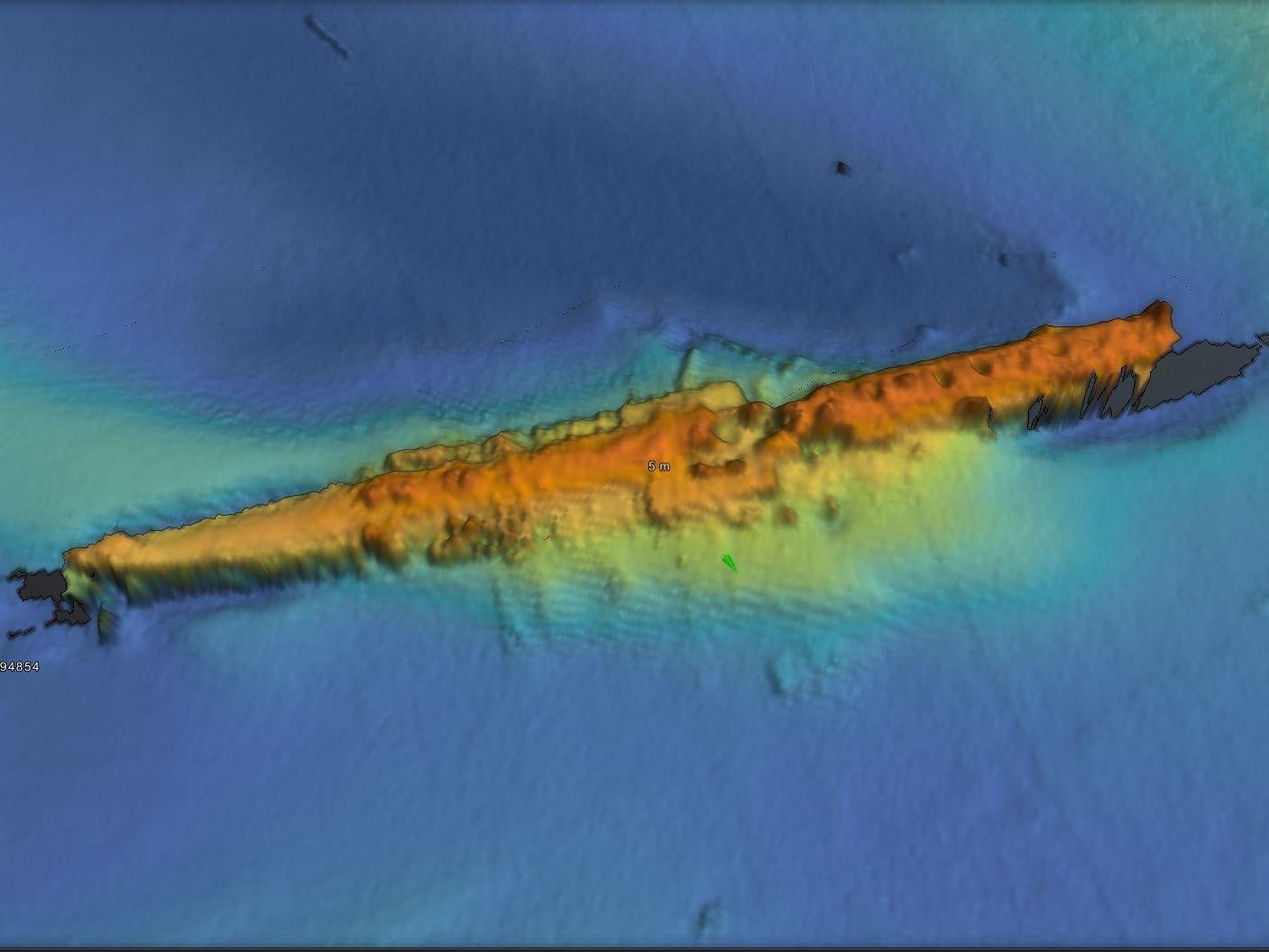

Using two remotely-operated unmanned modern submarines, the archaeologists – from the University of Southampton – have succeeded in making the first video and the first sonar 3D images of the forgotten wreck from the First World War.

The images, when combined with historical analysis, reveal the horrific final minutes of the German U-boat.

The underwater pictures show the damage done to the vessel when it was rammed and then repeatedly depth-charged by a royal navy vessel, Patrol Boat P57.

But the University of Southampton investigation – funded by the offshore gas industry infrastructure joint venture, Tolmount Development – is also revealing a series of mysteries about the long-forgotten German submarine.

Either during the First World War or after the conflict had ended, senior German naval officials believed that shortly after it was sunk, the royal navy had succeeded in obtaining secret papers from the wreck. The Germans believed that royal navy divers had entered the vessel and had recovered crucial intelligence information, including a detailed map of German minefields.

However, the University of Southampton investigation, led by archaeologist Dr Rodrigo Pacheco-Ruiz, has now assessed the wreck’s approximate depth in November 1917 (48-51 metres) – which suggests that diver penetration of the vessel was extremely unlike

Historical accounts reveal that HMS P57 spent several days dropping depth charges on the wreck.

It’s likely that this was done precisely because it was not possible to physically gain entry to the sunken U-boat. The only way to recover intelligence information was therefore to repeatedly depth charge her in the hope that additional holes in the vessel could be created – and that, as a result, important documents might then float to the surface.

Although there are no surviving British records of any such intelligence-gathering coup, senior German naval officials did know about it (although they wrongly assumed that the crucial papers had been recovered by royal navy divers – rather than as floating debris).

But how did they know? German historians, working in collaboration with the University of Southampton, are now planning to search the German archives to try to find an answer.

It is conceivable that the German navy had obtained the information by listening to royal navy wartime radio communications – or they may have somehow obtained it from British naval sources after the war.

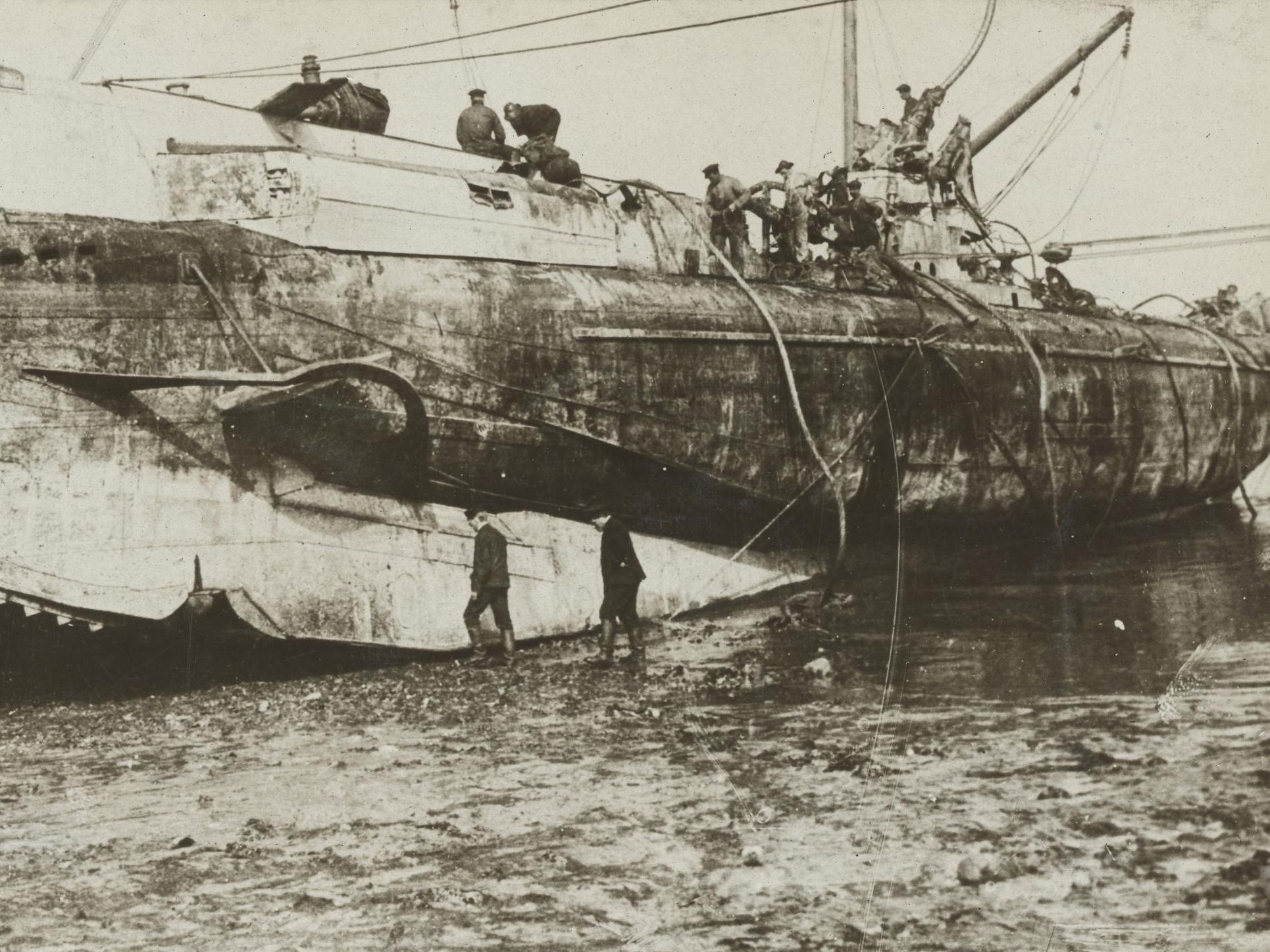

During the First World War, it was notoriously difficult to sink German U-boats. However, in late 1917 and 1918, the royal navy developed a number of techniques to reduce the impact of German submarines and to increase the number being sunk.

To reduce the German U-boat kill rates, they introduced the convoy system for UK merchant vessels – and to increase British success in destroying German U-boats, they fitted strengthened bows to royal navy anti-submarine vessels (to enable them to ram U-boats) and they developed the first effective depth charges.

Both new technologies were employed in the sinking of UC47.

And the repeated depth charge attacks on the sunken German submarine seems to have enabled the British to gain crucial intelligence information that would in turn have enabled them to locate and clear the mines that UC47, had laid (thus saving many UK merchant vessels from destruction).

The Germans primarily used their U-boats to damage the UK’s war effort – by seeking to blockade Britain and by trying to prevent the UK transporting vital coal, steel, timber and cement (much of which had to be transported from northern Britain to southern Britain by coastal cargo vessels).

It was in the second half of 1917 that the royal navy began to defeat the U-boat threat – and the sinking of UC 47 was an important part of that process – particularly so because that particular submarine was one of the most effective in the German navy. Prior to its sinking, it had sunk 56 UK and allied ships in just 13 months.

UC47’s end came on 18 November, 1917. All 26 of her crew went down with her. The historical record shows that, through sheer chance, the British patrol boat spotted the German U-boat about 200 yards away, approximately one hour before sunrise. Within 15 seconds, the royal navy vessel launched a devastating surprise attack on the German submarine by ramming her. The impact, at 17 knots, tore through the German vessel’s hull, causing her to start filling up with water. The British vessel then dropped two depth charges on the stricken sub – and quickly marked the position with a buoy.

A third depth charge was then dropped on the sunken U-boat – and a fourth was targeted at the German vessel as she lay on the seabed at 4pm on 19 November. Large amounts of oil and air bubbles continuously rose from the wreck to the surface. HMS P57 remained at the attack site for around three whole days. Even as late as 20 November, two days after the attack, personnel on board the British vessel saw very large air bubbles rising to the surface – so there were obviously still sizeable pockets of air in the sunken sub as she languished on the sea floor.

The two unmanned ultra-high-tech modern submarines used in the University of Southampton investigation of the German U-boat are operated by the Swedish offshore survey company, MMT – and owned by the Norwegian firm, Reach Subsea. The investigation into the wreck is being carried out by the university’s Centre for Maritime Archaeology, as part of that centre’s Offshore Archaeological Research programme.

“Our survey has revealed just how well preserved the wreck is,” said the archaeologist in charge of the investigation, Dr Pacheco-Ruiz of the University of Southampton‘s Centre for Maritime Archaeology.

“As our investigation continues, we hope to progressively shed more light on this long-forgotten deadly North Sea drama,” said the project’s historical adviser, Stephen Fisher.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario